SOUL OF A NATION

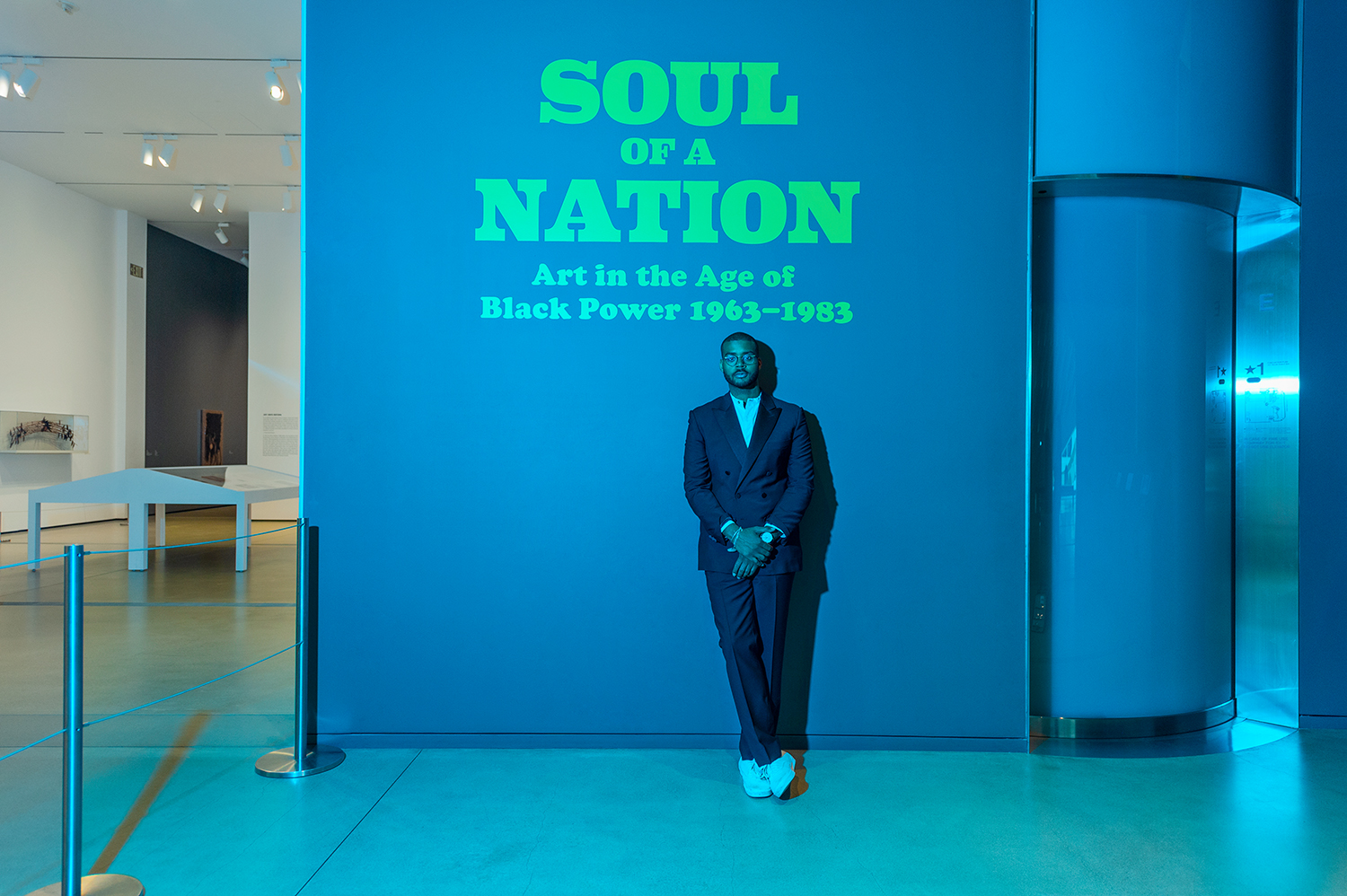

Bunker Hill— The west coast premiere of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 is now in its final month of exhibition at The Broad Museum. Officially, the show closes September 1st.

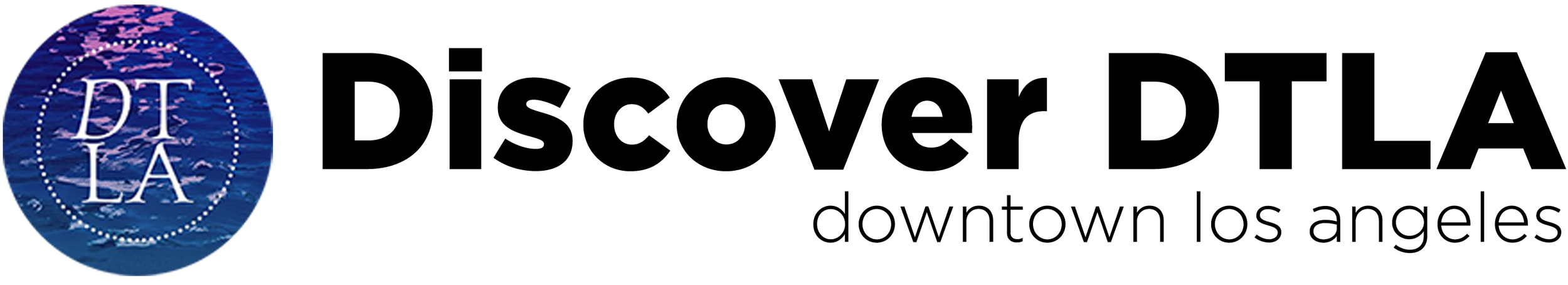

Soul of a Nation made a unique and lasting imprint on the City of Los Angeles through its exploration of an art movement that up until this point, had not received the undivided attention it deserved. Civil Rights in America always brings up powerful and dynamic images from our collective memory. However, most of today’s Americans have never experienced one of their country’s most iconic periods like this before.

It was our pleasure to walk through The Broad with Musician and Film Composer, Kris Bowers. Kris is a rising star in the cinema/television community having created powerful scores for Netflix’s Dear White People and When They See Us, which he recently received an Emmy nomination for. Perhaps most notably, Kris created the music for this year’s Best Picture, Green Book; including, performing all piano work required to accurately depict the great Dr. Donald Shirley. Read on for his perspective regarding the impact of Soul of a Nation:

What made you want to come and see the show?

I’ve always been fascinated by African American artists because I’m always curious how other artists represent the black experience through their medium; especially visual art because it’s very different than music, but at the same time there are so many similarities.

Do you find universal themes here that apply today?

Yeah, definitely. There is still this idea of celebration: celebration of history, celebration of heroes, leaders and things like that. There’s still the idea of this militant attitude. I think some of these paintings might be inspired by the Black Panther Party, which is not too dissimilar to Kendrick Lamar as far as that attitude and edge.

There’s a lot more art here showing how painful that period was because obviously the period in the 60s, and during the Civil Rights era, was a lot more painful, or slightly more painful than it is now, because it’s still pretty painful sometimes, but it’s interesting to see that there are still those parallels, for sure.

Do you notice any distinct differences?

I think there’s a lot more minimalism in the art (today) that I’ve seen. I’m not by any means a historian or an expert at all, but when I look at people like Glenn Ligon or even Hank Willis Thomas there’s a different approach, and the mediums feel a little less gritty. A lot of this stuff feels raw in an interesting way.

It’s interesting to see how much it parallels the music that was happening at that time. We were listening to the Quincy Jones playlist, but all the Jazz of the late 60s and early 70s was starting to get so abstract; the jazz in the 50s and the early 60s was all about being cool. It just had a different feel to it, it wasn’t as angry or as visceral as the music in the late 60s and 70s. It’s interesting to see the art that was being made at that same time.

What did you think about Quincy’s playlist?

Yeah, it was pretty awesome! (He smiles) I think one of the things that was always lacking in music education, especially Jazz education, is the context that the music was created in– the time period, what these people are going through, why they were creating the kind of music they were creating. It’s really cool to be able to walk through and listen to the music while looking at this art because it helps make that context.

How is it to see the visual counterparts to the music you’ve studied?

We’re sitting next to this piece that’s inspired by Trane (John Coltrane). Knowing that’s what the artist was inspired by makes a bunch of sense because there are all these angles to it and different colors, which I think shows how Trane was very methodical. These all might be angles and colors but it doesn’t look mathematical, it doesn’t feel mathematical, it feels organic, which I think is what Trane did best. He figured out how to take incredibly technical music and make it feel organic.

There’s another section that talked about being inspired by the improvisation nature of the late 60s and early 70s. The free form aspect of that music you can see in a lot of the art.

What do you take away from the show?

I found it interesting to see some of these pieces that are obviously created from the black viewpoint or experience, but at the same time might not be overtly “black”. I was reading that a lot of people felt they didn’t showcase the black experience in the way people at that time thought that they should.

That’s something I’m always curious about in my own art because at the end of the day I feel like a person of the world. That being said, I’m still a black man and I’ve had that experience, so trying to figure out how to present both of those things in an equal way is always something I’ve thought about and struggled with on some level.

How would you like future generations to view your work?

I’m inspired by a lot of things that are outside the black experience, or maybe aren’t defined as black art. I’m just as inspired by Steve Reich as I am by Thelonious Monk. I’ve always been trying to figure out how to enfuse all of that together in my art.

There are some amazing artists that don’t care about anything else outside of that experience (African American Experience) but I do think that there’s so much out there, that might show you a bit more. For example, going back to my inspiration of Steve Reich, I listen to Steve Reich and I hear hip-hop samples.

If you’re an artist, you can’t separate yourself from your background or where you come from. The way you see the world is directly informed by your surroundings and your upbringing. Don’t be afraid to look at anything, because at the end of the day it’s all going to come through your lens, your point of view and your voice.

What was your experience like here at The Broad?

It’s my first time at The Broad, which I’m ashamed to say, but it was a pretty special way to see it for the first time. It was really cool to see how the space feels and how it’s been shaped. It’s been a pretty amazing experience!

Soul of a Nation is on view through September 1st. Get tickets at thebroad.org